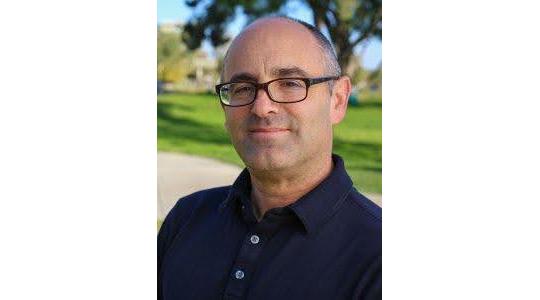

Lori G. Beaman, Ph.D., is the Canada Research Chair in Religious Diversity and Social Change, Professor in the Department of Classics and Religious Studies at the University of Ottawa (Canada), and Director of the Nonreligion in a Complex Future (NCF) project.

Lori G. Beaman, Ph.D., is the Canada Research Chair in Religious Diversity and Social Change, Professor in the Department of Classics and Religious Studies at the University of Ottawa (Canada), and Director of the Nonreligion in a Complex Future (NCF) project. The NCF project is an international, comparative, interdisciplinary research project which identifies the social impact of the rapid and dramatic increase of nonreligion in Canada, Australia, the Nordic countries (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland), the United States, the United Kingdom, and Latin America (Brazil and Argentina).

Prof. Beaman’s publications include The Transition of Religion to Culture in Law and Public Discourse (Routledge, 2020); Deep Equality in an Era of Religious Diversity (Oxford University Press, 2017); edited with Timothy Stacey, Nonreligious Imaginaries of World-Repairing: Studying an Emergent Majority (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021); “Religion to Culture: Who is the ‘Us’,” Cultural Studies 38, no. 5 (2024): 750-771; and, co-authored with Chris Miller, “Nonreligious Afterlife: Emerging Understandings of Death and Dying,” Religions, 15, no. 104 (2024). Her current and engaged areas of research include nonreligion, human/non-human relationships, equality, law, and religious diversity.

Areas of expertise:

Nonreligion, human/non-human relationships, equality, law, and religious diversity